Brown trout are one of the most coveted sport fish in the world. They are loved for the variety of beautiful patterns, colors, and shapes they exhibit. Even with a quick look at my gallery page, you can see how different they can look from each other. They are a versatile species that have created many native populations throughout the US since their introduction. In this post, I hope to offer you some general knowledge of the great brown trout.

Quick School Lesson

The brown trout (Salmo trutta) is a cold-water fish species (32-68 F) that inhabits all types of water. In lakes or oceans, they are usually found in the thermocline, the layer of water where water temperatures drop rapidly. In moving waterways, they are found in spring fed creeks with cold water supplied from below the earth’s surface. In these habitats, they are opportunistic sight feeders, meaning they have a varied diet based on their visual environment, making them an excellent subject for fly-fishing. They typically live up to 12 years and can spawn multiple times in their lifespan. If you want to learn about where you can find them near you and public fishing access, check out your local conservation site. For NYS, check out New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (ny.gov)

History of the Brown Trout

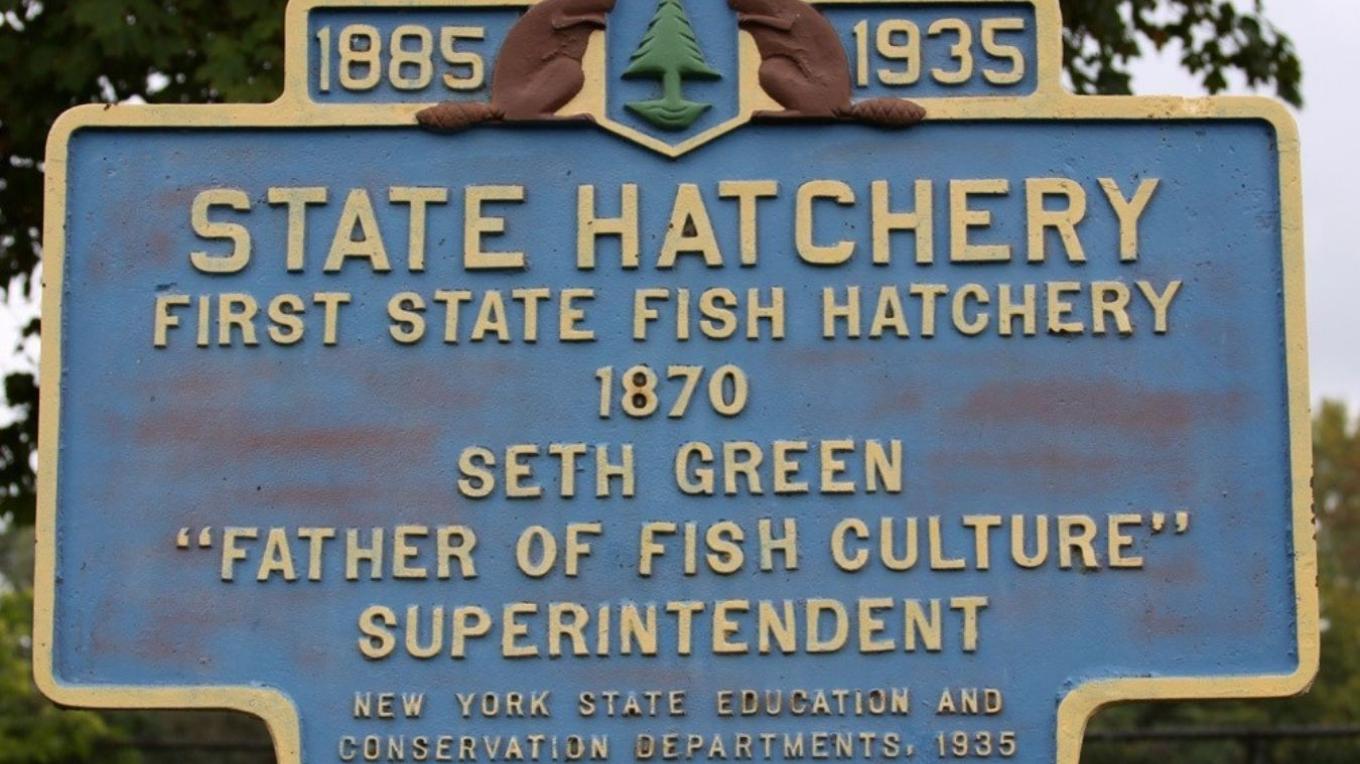

What many fans of the brown trout don’t know is that they are non-native to the United States. All of the brown trout in the rivers, streams, lakes, and oceans in the US are genetic descendants of European or Western Asian populations. In the 1880’s brown trout were shipped across the Atlantic Ocean to New York City for the implantation of new populations across America. One of the first few shipments arrived in my very own Rochester, NY, in a small town called Caledonia. The hatchery in Caledonia is still in operation today. It flows into Spring Creek which holds established trout populations as well as yearly stockings. Since the 1880s, brown trout populations have wandered (or been stocked) into most bodies of cold water.

To put that in perspective, brown trout were in the US before the Statue of Liberty was finished, or if you are into pop-culture, brown trout were introduced during the same time period depicted in the newly famous Yellowstone prequel, 1883. Pretty amazing if you ask me because these were the first genetic pools of brown trout, which are now found in almost every state, and they were instated by folks riding the horse and buggy – a testament to the adaptability of these fish.

Wild vs Stocked Fish

To experienced anglers there is a known distinction between catching a wild brown and a stocker. “Wild browns” are typically in reference to fish from self-sustaining populations that are a few generations post stock. Wild populations typically have certain characteristics that stocked browns do not have and thus are more desirable. For example, wild browns typically have more vibrant colors, sharper fins, and are usually smaller in size. Take a look at these two catches from a few years back. Can you tell which one is wild?

The real key to knowing if one is wild or not is the catch location. Stocking data is public, so if you catch brown trout in an area that hasn’t been stocked in years, you can be pretty confident you found a wild brown.

Anadromous?

The word anadromous is one of those words you just read over because you don’t know what it means. However, I love fishing and I couldn’t brush over this word like some other vocabulary challengers. It was a necessary part of learning how to catch trophy brown trout because it describes an important behavior. Anadromous is an adjective that is used to describe the behavior of migrating from the sea (or lake) to the river for reproduction. There are anadromous brown trout and resident brown trout. Resident brown trout stay in streams year-round but typically reproduce at the same time. This reproduction cycle is typically in the fall creating a “fall-run” for anadromous browns.

Why is that important to know? Well, for me it means bigger fish. If you imagine the food source in a large body of water compared to streams, it is a no-brainer that fish get bigger. Think of goldfish in different sized bowls or some house plants in different sized pots. So, if you know they are coming in the fall and what they’re doing, then you can make some important decisions regarding fly-fishing for them. More on that regard in my other blogs and future posts to come.

It also explains genetic diversity because migratory fish can reproduce with resident fish, therefore a great advantage for genetic distribution. Genetic diversity manifests in the many patterns, colors, and shapes of the fish as well as unseen characteristics such as behavior.

Recommendations

As you can tell, I like learning about the fish that I spend hours attempting to catch. In my opinion, even learning a few things can translate into catching more fish. Take my anadromous section as an example. If large fish are running into rivers to spawn, then there will be a large food source of fish eggs for the post-spawn fish to eat. If I know this then I can look at the color of real eggs and then tie something on to mimic it.

Or using the short biology lesson. If you dig a little deeper into their behavior in different environments, you may stumble upon great research or blog posts that explain some of their behaviors with biological factors like their eyes or sense of smell. With this knowledge you can apply it on your local waterways to catch (and release) more fish.